Using Ruby enum_for to implement multiple paths enumerating the same Enumerable

Idiomatic breadth-first versus depth-first tree-traversals in Ruby

Anyone who has gotten very far in a basic “implement this data structure” tech-screen, using Ruby, hopefully knows about just making your class an Enumerable and implementing #each to get all of the methods of that Mixin, which people are used to using on collections in any Ruby project. Less obvious is how you tackle a more complex case, like trees (another interview classic), which have different possible traversal methods of even the same instance.

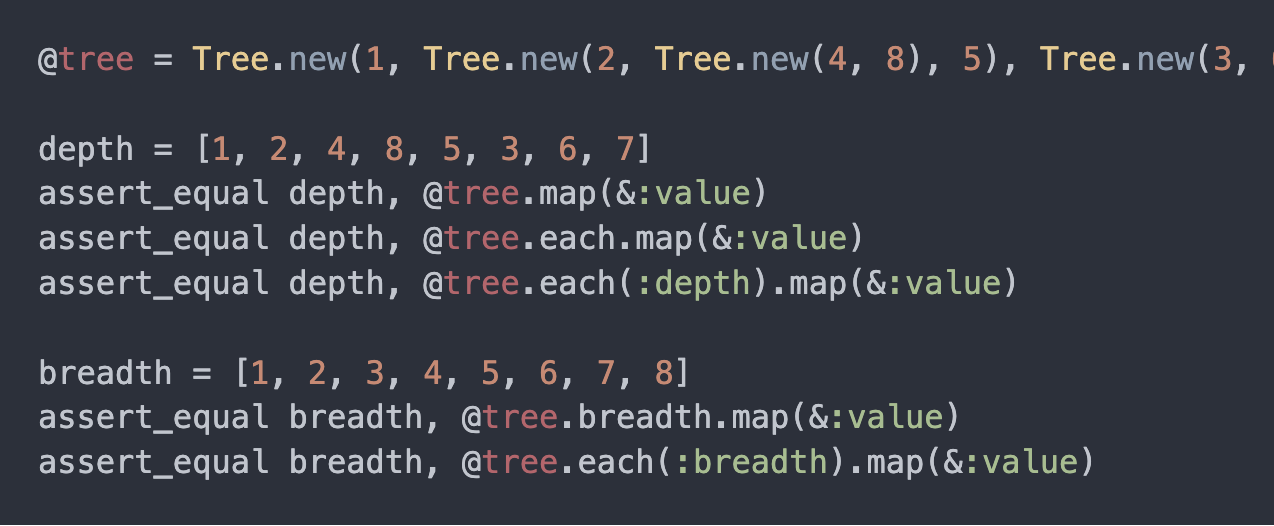

In this post I’ll show how to use enum_for to make an interface for a Tree class that supports these different styles of usage for traversals:

@tree = Tree.new(1, Tree.new(2, Tree.new(4, 8), 5), Tree.new(3, 6, 7))

depth = [1, 2, 4, 8, 5, 3, 6, 7]

assert_equal depth, @tree.map(&:value)

assert_equal depth, @tree.each.map(&:value)

assert_equal depth, @tree.each(:depth).map(&:value)

breadth = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

assert_equal breadth, @tree.breadth.map(&:value)

assert_equal breadth, @tree.each(:breadth).map(&:value)

I’ve given the LinkedList version of a tech screen enough times (before I decided the flaws in this whole approach outweigh the gains, but that’s a longer topic for another post), so I could probably implement it in my sleep. Since I’ve been working on learning Rust, I practiced some list implementations in that. This was excellent didactic experience (I learned so much more about Option and why I really do like Rust), but it definitely highlighted that I don’t have the 20 years experience in Rust that I do in Ruby.

Whipping out a LinkedList to reminded myself that yes, I still know Ruby very well (it descended into golfing, and then this slightly silly implementation of #unshift that I’d never do outside a gag: l,s = reverse_each.first(2); l.h.tap { l.h = s&.t = nil }). I figured I should do tree traversals as well, since breadth-first did trip me up in an interview once (I choked and couldn’t recall “just put it in a stack”, which I have since tattoed into my brain).

The interesting part is right here:

def each(traversal=:depth, &block)

case traversal

when :depth

depth(&block)

when :breadth

breadth(&block)

else

raise "Why don't *you* implement #{traversal} traversal"

end

end

def depth(&block)

return enum_for(:depth) unless block_given?

yield self

children.each { |c| c.each(&block) }

end

def breadth

return enum_for(:breadth) unless block_given?

stack = [self]

while current = stack.shift do

yield current

stack.push *current.children

end

end

By returning an Enumerator from your arbitrarily named (unlike implementing Enumerable via #each) traversal methods, you allow them to be chained as usual with #map (or any of the other similar methods). And you can then just call these methods directly from your #each implementation, making the enumerable methods work when called directly on an instance of the class (defaulting to depth).

Oh also make sure to deref/splat the children into your stack on breadth, so you don’t mutate the children list directly. I didn’t catch that till I added the tests to make sure you could repeat traversals safely. Which shows that tests are nice… but Rust would have caught that upfront (but also made this all quite a bit trickier. Tradeoffs).

In case it’s of interest, here’s the rest of the basic class:

#how inspect looks, from a test. I think I need to tweak it a bit more to make it more intuitive.

assert_equal "1: [2: [4: [8], 5], 3: [6, 7]]", @tree.inspect

#the thing itself

class Tree

include Enumerable

attr_accessor :children, :value

def self.new(value, *children)

value.is_a?(Tree) ? value : super(value, *children)

end

def initialize(value, *children)

@children = *children.map { |c| Tree.new(c) }

@value = value

end

def inspect

if children.empty?

value.to_s

else

"#{value}: [#{children.map(&:inspect).join(', ')}]"

end

end

By overloading #new to either make a new Tree (and call #super, of course, don’t skip your #allocate) or just pass along the existing one, we make trival the test setup in the first code block that just passes the nested trees in directly as children, as well as the literal values. Oh and *splat the children again, of course, this time so you can pass in an arbitrary amount.